A Clockwork Orange (1971): Free Will in Chains

Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange is as controversial today as it was upon its release in 1971. Based on Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel, the film is a bold, deeply unsettling exploration of violence, psychological conditioning, and the loss of free will. Set in a dystopian future Britain, it holds up a mirror to society’s contradictions—especially its attempts to control behavior through force and manipulation.

The story revolves around Alex DeLarge, a teenage delinquent who leads a gang of “droogs” through nights of assault, theft, and extreme violence. Alex is not simply a thug; he’s a paradox. He’s articulate, intelligent, loves classical music—particularly Beethoven—and speaks in an invented slang called Nadsat. But he’s also cruel, sadistic, and disturbingly charismatic. Kubrick uses this juxtaposition to challenge viewers: we’re repulsed by Alex’s actions, but at times, uncomfortably fascinated by him.

In the first act, we witness Alex and his gang committing horrifying acts of “ultraviolence,” including a home invasion, a brutal beating, and a rape. Kubrick’s use of stylized violence—slow motion, classical music, surreal sets—makes these scenes both revolting and hypnotic. It’s a dangerous line, and the film has been criticized for aestheticizing brutality. But Kubrick’s intention is not to glorify violence. Rather, he asks what it means when society becomes complicit in the spectacle of cruelty.

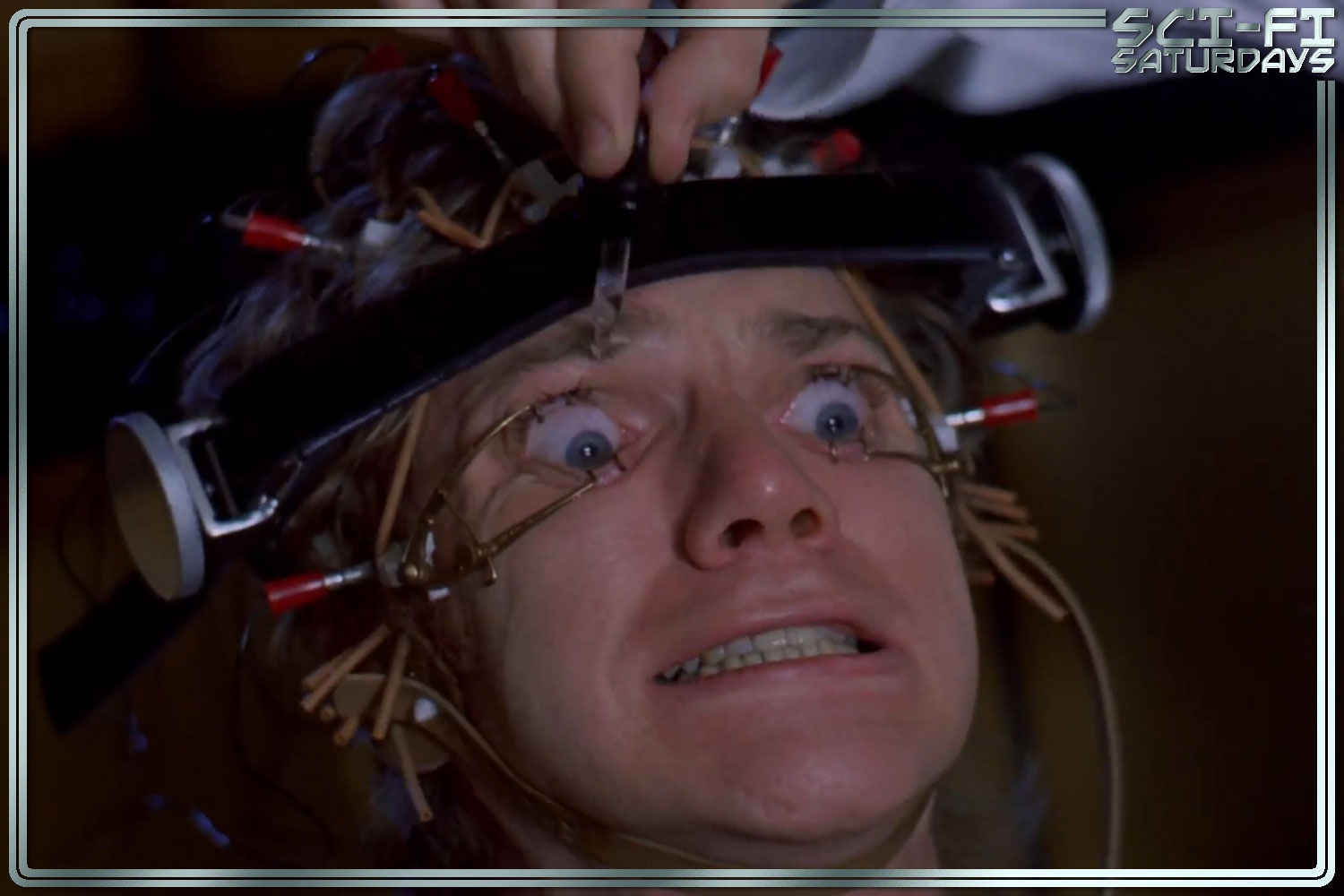

Alex’s luck runs out when he kills a woman during a botched robbery. Betrayed by his droogs and arrested, he is sentenced to prison. There, he volunteers for the Ludovico Technique, a controversial form of psychological reconditioning. The process is horrifying: Alex is strapped to a chair, eyelids forced open, while he's made to watch hours of violent and sexual imagery. Meanwhile, a drug induces severe nausea, permanently linking violent thoughts to physical sickness. Even Beethoven, once a source of spiritual ecstasy for Alex, becomes a trigger for pain.

When Alex is released, “cured” of his criminal impulses, the world he returns to is unrecognizable. His parents have replaced him. Former victims turn on him. The government, eager for good PR, uses Alex as proof that their social experiments work. But the cost is immense. Alex has lost the ability to choose. He is incapable of defending himself or expressing his desires. He is no longer human in the full sense—he is, as the title implies, a “clockwork orange”: organic on the outside, but mechanical within.

Kubrick’s core question emerges here: Is it morally right to take away a person’s ability to choose—even if it means eliminating their ability to do harm? The film strongly suggests that morality without choice is meaningless. Alex, for all his monstrous behavior, was at least choosing to act. Post-treatment, he can only react.

The film's final act is a brutal satire of both government and morality. A left-wing writer, whose wife was raped by Alex, takes him in—only to realize Alex is the same assailant. In an ironic twist of revenge, he uses Beethoven’s music to drive Alex to attempted suicide. Alex survives and becomes a political pawn. To avoid scandal, the government undoes the Ludovico conditioning. The film ends with Alex smiling, imagining violent fantasies again. He says, “I was cured, all right.”

This closing line is dripping with irony. Alex is back to his old self, but Kubrick leaves us in doubt about whether this is justice, tragedy, or the lesser of two evils. Has Alex changed, or is the system so flawed that it can only undo its own failures by reinstating evil?

Kubrick’s direction is clinical, stylish, and provocative. The visuals are striking: stark interiors, futuristic fashion, and eerie, exaggerated lighting all contribute to an atmosphere of unreality. The soundtrack, featuring classical compositions and Moog synthesizers, underscores the tension between chaos and order. The music becomes part of the character of the film itself—both elegant and dissonant.

Malcolm McDowell delivers a career-defining performance as Alex. He’s magnetic, terrifying, and, disturbingly, often likable. This contradiction is the film’s engine. Kubrick forces us to empathize with someone who embodies everything we should condemn. That discomfort is intentional. It's a confrontation between our values and our instincts.

Critically, the film was divisive upon release. Some hailed it as a masterpiece; others condemned it as dangerous and morally irresponsible. In the UK, it was withdrawn from circulation by Kubrick himself for decades due to alleged copycat crimes. But time has reframed the film as a complex philosophical work rather than a glorification of violence.

Burgess, the novel’s author, famously disliked Kubrick’s adaptation, particularly because it omits the book’s final, redemptive chapter in which Alex genuinely outgrows his violent urges. Kubrick deliberately excluded that ending to maintain the ambiguity and bleakness. In his version, the cycle of violence continues, and the film becomes a critique not only of individual behavior, but of how society responds to it—with punishment instead of understanding, control instead of compassion.

In many ways, A Clockwork Orange is about institutions: the prison system, the media, the medical establishment, and the government. Each, in its own way, fails. Each attempts to solve the problem of human violence by denying humanity itself. Kubrick doesn’t offer answers—only questions, often uncomfortable ones.

Why do we punish the violent with more violence? Is a man who cannot choose evil still capable of choosing good? What is the difference between reform and repression? And when society seeks peace through control, is it any more moral than the individuals it condemns?

Today, A Clockwork Orange remains disturbing, challenging, and deeply relevant. It asks us to look beyond the sensational surface—to consider the cost of security, the meaning of freedom, and the fragility of human morality when reduced to policy. It's not a film that comforts. It's a film that provokes—and that's precisely why it endures.

-1751271843-q80.webp)