In the landscape of body horror and dark satire, Teeth (2007) stands out not just for its infamous premise, but for how it dares to challenge and reclaim the genre. Written and directed by Mitchell Lichtenstein, the film takes a bold, grotesque, and often darkly funny look at female empowerment, sexuality, and repression. At its center is a girl with a dangerous secret—and a monstrous gift she never asked for.

While it may be remembered by some as "the movie about a vagina with teeth," Teeth is far more than a gimmick. It’s a provocative, layered, and uncomfortable coming-of-age story that has become a cult classic for a reason.

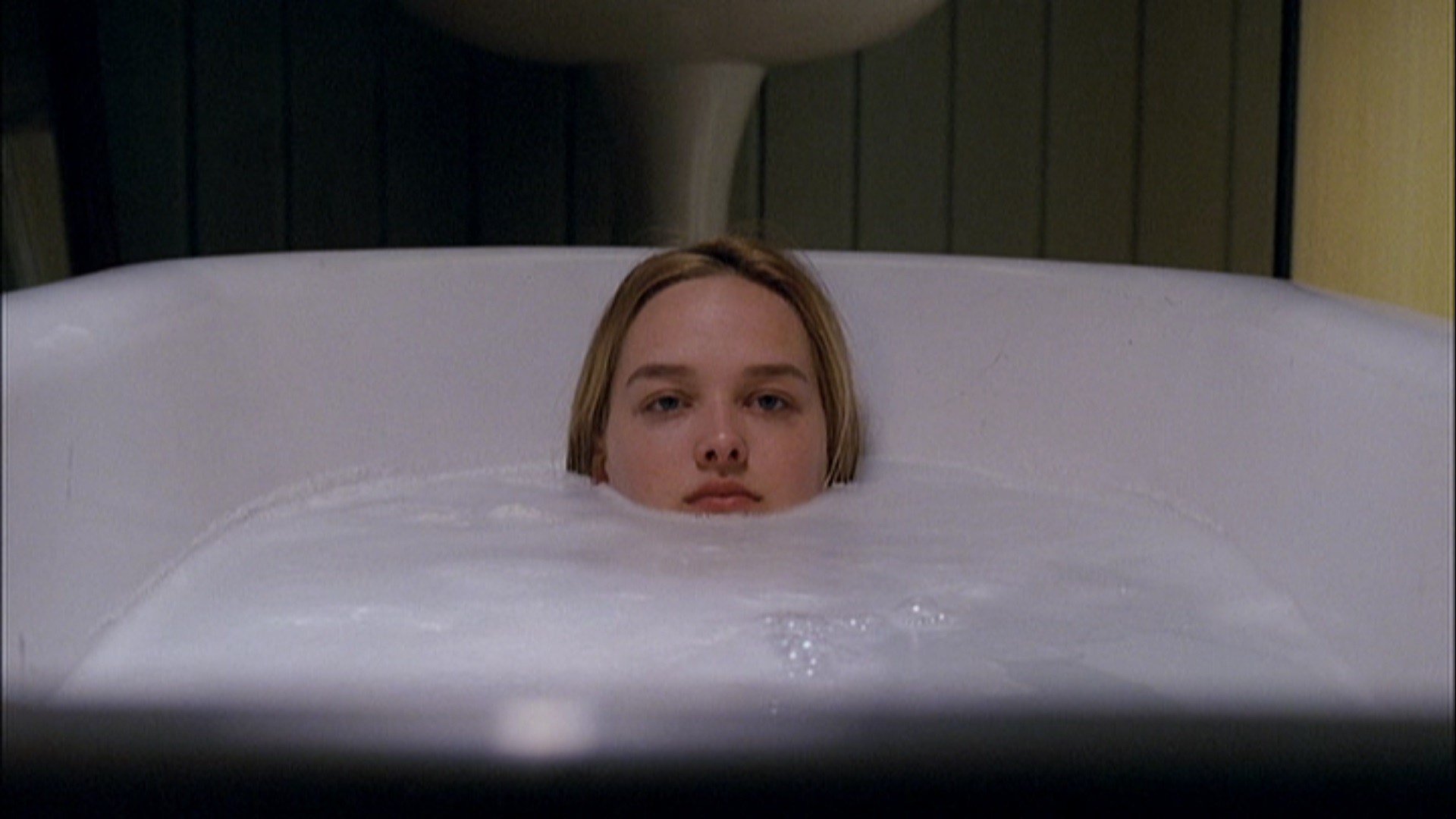

The story follows Dawn O’Keefe (played by Jess Weixler), a high school student and outspoken advocate of abstinence and purity. Living in a conservative small town and surrounded by pressures to stay "pure," Dawn believes in saving herself for marriage—and leads talks at her local youth purity group.

But there’s something unusual about her body that even she doesn’t understand. When she begins to explore intimacy for the first time, the results are—unexpected. A traumatic encounter with a boy turns violent, and Dawn's body reacts in self-defense: she discovers she has vagina dentata—a mythical condition where her genitals literally bite back.

From that moment, Dawn begins a journey of fear, self-discovery, and vengeance. As more men around her reveal themselves to be manipulative, violent, or worse, her body becomes her weapon. At first terrified by it, she eventually learns to harness her unique anatomy—not just for protection, but for justice.

While the plot sounds absurd on paper, Teeth plays it mostly straight, walking a tightrope between horror, black comedy, and social critique. It’s not just about gore or shock—it’s about what happens when a girl, raised to feel shame about her body and sexuality, discovers she cannot be controlled.

Mitchell Lichtenstein uses horror tropes to subvert rather than reinforce misogynistic ideas. Every "victim" of Dawn’s body is a man who has tried to manipulate, assault, or harm her. The film inverts the usual dynamic of horror movies, where women are often punished for sexual activity. In Teeth, it is the abuser who bleeds.

Dawn’s body is not cursed—it is her strength, albeit one she must first come to understand. Her evolution from confused victim to confident avenger is the film’s true arc. In many ways, it's a superhero origin story masquerading as a grotesque B-movie.

Jess Weixler’s performance is the emotional anchor of the film. She captures Dawn’s journey with sensitivity and courage—from naivety and fear to rage and resolve. Her expressions of horror, confusion, and eventually eerie calm help elevate the movie from exploitation to introspection. She won a Special Jury Prize at Sundance for her work, and deservedly so.

The supporting cast leans into the satire—especially the men, who range from clueless to predatory. The film doesn’t offer many safe male characters, but that’s intentional; it paints a portrait of a world where women are taught to be quiet and polite, even as they’re threatened at every turn

Visually, Teeth is grounded and modest, but moments of violence are handled with an almost clinical tension. The camera never lingers for too long on the gore, instead leaving the worst to imagination—and that’s where it’s most effective

Teeth is a film about control. It asks: who owns a woman’s body? What happens when the body fights back? And why are we so afraid of female power?

Dawn begins the film as someone whose identity is defined by repression. She covers her body, avoids sexual conversation, and fears the natural impulses she begins to feel. But as she sheds those fears—often through painful, violent encounters—she learns to reclaim what she was told to hate.

The film also critiques the idea of male entitlement, particularly in scenes where men attempt to assert power over Dawn. But with each betrayal, each assault, her body responds automatically—becoming a metaphor for self-protection and the refusal to be victimized.

Teeth is not for everyone. It’s provocative, at times deeply uncomfortable, and it forces viewers to question where they draw the line between horror and empowerment. But for those willing to engage with its message, it offers something rare: a horror movie that gives power back to the powerless.

It remains a cult classic because it dares to talk about things most horror films shy away from: consent, shame, autonomy, and revenge. And it does so with humor, horror, and unapologetic sharpness. At the end of Teeth, Dawn smiles—not in fear, but in control. She’s no longer the girl who needs saving. She is the reckoning.