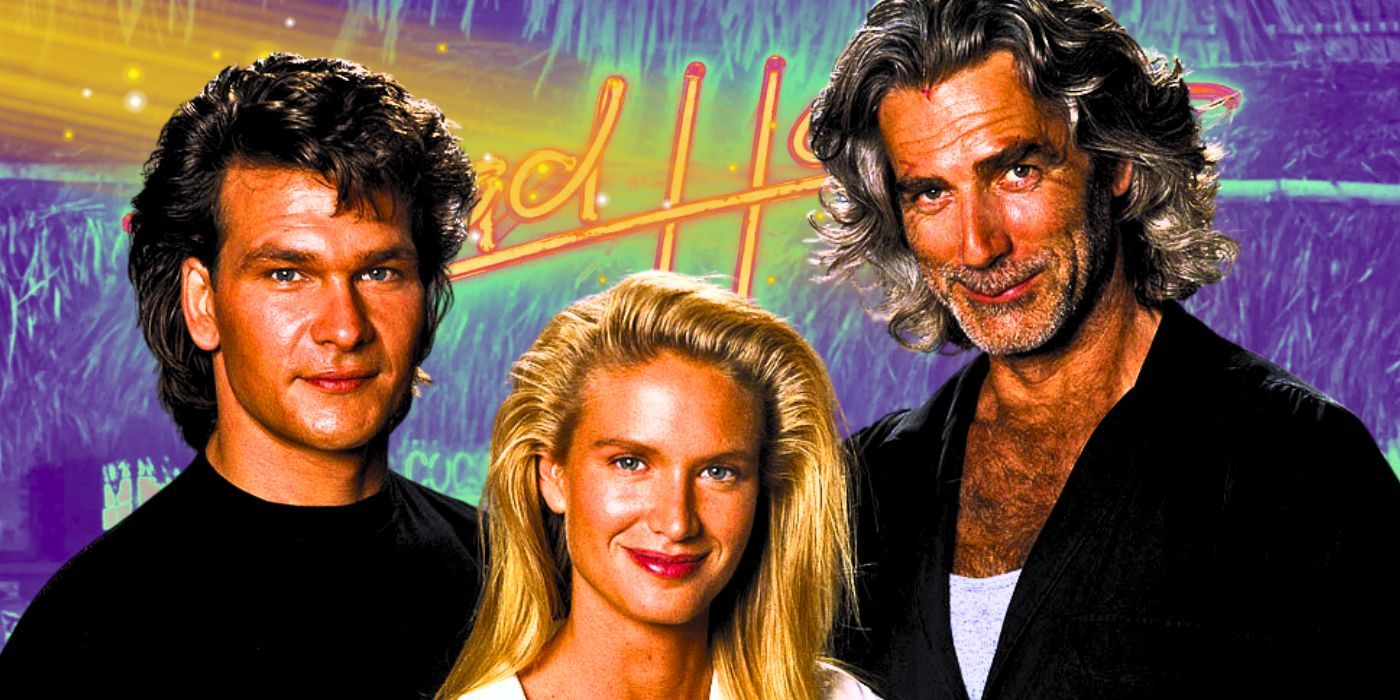

Few action movies from the 1980s are as gloriously strange, unexpectedly deep, and relentlessly entertaining as Road House (1989). Directed by Rowdy Herrington and starring Patrick Swayze at the height of his post-Dirty Dancing stardom, the film has since achieved cult status — and not just because of its bar fights, explosions, and denim-heavy wardrobe. Beneath its surface of flying fists and broken beer bottles lies something more eccentric and oddly thoughtful: a martial arts Western disguised as a bouncer movie.

The plot is simple and mythic, as most good cult films are. Dalton (Swayze) is a “cooler” — the zen master of nightclub security — hired to clean up the Double Deuce, a rowdy roadside bar in small-town Missouri overrun by violence, drug deals, and broken furniture. But as Dalton brings order to the chaos, he uncovers a deeper rot: the town is under the grip of a local tyrant, Brad Wesley (Ben Gazzara), a man who runs a criminal empire with impunity and treats the town as his personal fiefdom.

Dalton, soft-spoken but deadly, becomes a kind of vigilante philosopher. He refuses to carry a gun. He practices tai chi in the morning sun. He speaks softly, smiles politely, and follows a strict code: “Be nice… until it’s time to not be nice.” He’s not just a bouncer — he’s a moral compass in a town that’s lost its way. And in true Western fashion, he becomes the reluctant hero who must restore justice by confronting the outlaw who controls everything.

What makes Road House stand apart from other action films of its time is the tone — a strange mix of pulpy violence, sincere character drama, and camp. It’s a film that knows it’s ridiculous and leans into that without turning into parody. Patrick Swayze plays Dalton completely straight, and it works. He’s charismatic, magnetic, and completely committed to the role. He fights with elegance and precision, but there’s also a tragic depth to the character. We learn he once killed a man in self-defense and has been trying to live with the consequences ever since. He’s a warrior trying to outrun his past, but violence keeps finding him.

The supporting cast adds texture to the dusty, neon-lit world of Road House. Sam Elliott steals every scene as Wade Garrett, Dalton’s mentor and fellow “cooler,” whose arrival brings both fatherly wisdom and a harsh dose of reality. Kelly Lynch plays Dr. Elizabeth Clay, Dalton’s love interest, who is drawn to his intelligence but increasingly disturbed by his capacity for violence. And Ben Gazzara’s Brad Wesley is one of the great scenery-chewing villains of ‘80s cinema — smug, rich, and casually cruel. He flies helicopters over people’s homes for fun. He kills without remorse. He’s capitalism with a cigar and a smirk.

Visually, the film embraces its late-’80s aesthetic with pride. The Double Deuce transforms over the course of the film from a literal war zone into a sleek, functioning honky-tonk. The fight choreography, particularly for the time, is fluid and brutal. Fists crunch, bodies fly, tables shatter. Yet for all the violence, there’s a strange beauty to it — especially when paired with Dalton’s Eastern-influenced fighting style and the rock-and-blues soundtrack that pulses in the background.

Of course, Road House is not without its absurdities. Some of its dialogue borders on legendary cheese (“I used to fuck guys like you in prison” has become one of the most famously jarring lines in action history). The plot escalates from bar fights to machine guns almost without warning. There are moments where it feels like three different movies stitched together: a romantic drama, a kung fu flick, and a Western revenge story. But rather than sinking under its tonal shifts, Road House thrives on them. It doesn’t care about realism — it cares about myth.

The myth, in this case, is the American lone hero — a man who walks into a corrupt town, enforces his own code of justice, and leaves once peace is restored. It’s the same story told in Shane, High Noon, and The Outlaw Josey Wales, but with mullets, motorcycles, and monster trucks. It’s no coincidence that the film ends with a naked brawl in a taxidermy-filled trophy room, followed by an old-fashioned showdown where the townsfolk finally take up arms against Wesley. In the end, it’s not Dalton who kills the villain — it’s the people he inspired.

If there were ever a sequel or spiritual continuation of Road House, it wouldn’t need to be bigger — it would need to be quieter. A story about what happens after the hero walks away. Perhaps we find Dalton years later, living off-grid, haunted by violence, resisting the urge to get pulled into another fight. Maybe he meets a younger version of himself — someone just as angry, just as idealistic — and has to choose whether to train him or warn him away. The conflict would be internal: can you live in peace when all you’ve known is violence?

In a modern age of hyper-stylized action films and comic-book franchises, Road House endures because it’s so specific. It’s not a movie that could be made today — at least not with the same balance of sincerity and swagger. Its mix of brutal action and poetic introspection is rare. It’s a film that doesn’t wink at the audience, even when it's at its most outrageous. It plays every scene like it means it.

And maybe that’s why it works.

Because beneath the beer bottles, punches, and explosions, Road House is a movie about a man trying to live by a code in a world that doesn’t want him to. And in that way, Dalton isn’t just a bouncer — he’s a ronin, a gunslinger, a samurai in denim.

Pain don’t hurt. But losing your way does.