When No Country for Old Men arrived in 2007, it didn’t just mark a return to form for the Coen Brothers—it redefined what audiences could expect from a thriller. Adapted from Cormac McCarthy’s sparse and brutal novel, the film is a meditation on violence, fate, morality, and aging in a world that no longer makes sense to the men sworn to protect it.

Now, nearly two decades later, the film’s quiet nihilism and chilling execution still hit like a sledgehammer. It’s not just a great film—it’s a modern classic, a slow-burning Western with the soul of a horror story.

Set in the dusty desolation of 1980s West Texas, No Country for Old Men opens with Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a welder and Vietnam vet, stumbling across a drug deal gone wrong while hunting antelope. Among the corpses and wrecked trucks, he finds a briefcase filled with $2 million in cash. Against better judgment, he takes it—and thus triggers a violent, relentless chase.

On his trail is Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), a psychopathic hitman armed with a cattle bolt gun and a code of ethics as strange as it is terrifying. Chigurh doesn’t just kill for money—he kills to restore balance in a world he sees as ruled by chance. He is the embodiment of death, unpredictable yet inevitable.

Meanwhile, aging sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) watches the bloodshed unfold with a mix of helplessness and despair. He can’t keep up. He doesn’t understand the evil he’s witnessing. And more than anything, he no longer believes the world has a place for men like him—men with rules, with honor, with hope.

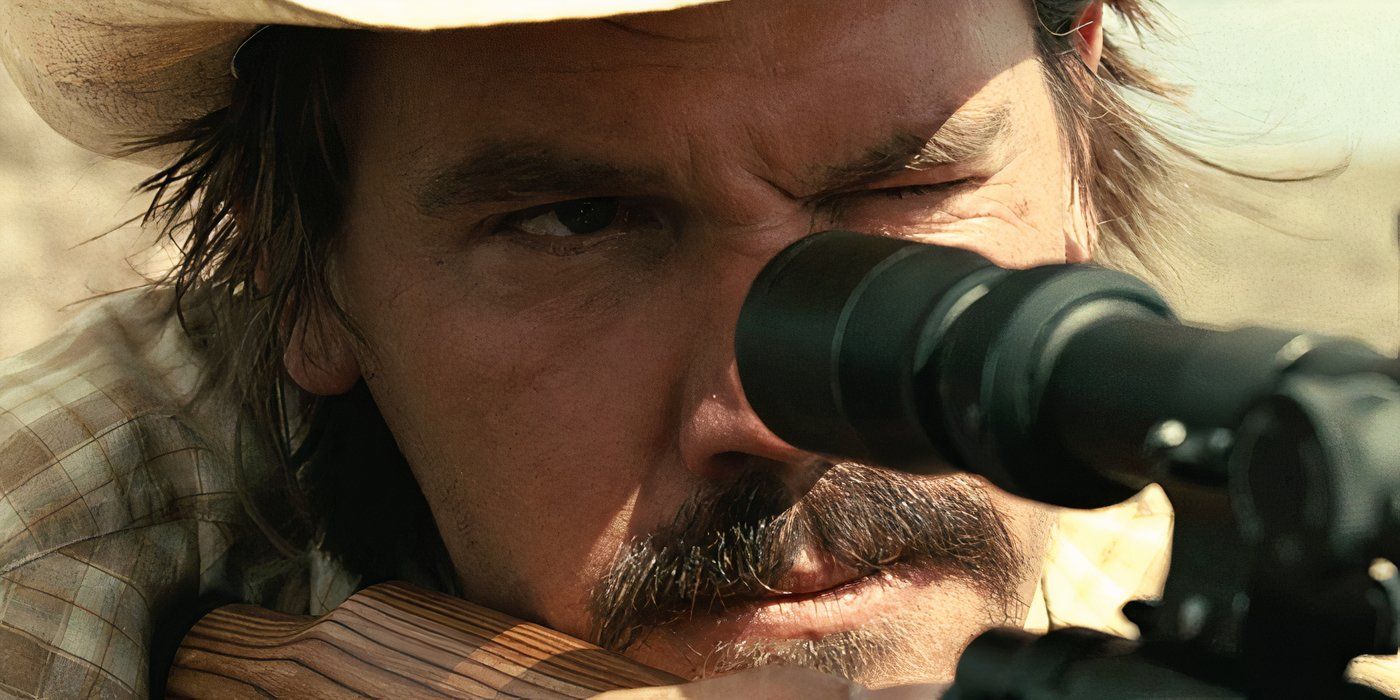

Javier Bardem’s portrayal of Chigurh is the film’s beating, icy heart. With his unsettling bowl cut, dead eyes, and calm monotone, he crafts one of cinema’s most terrifying villains. Every time he flips a coin, the air tightens. He doesn’t shout. He doesn’t threaten. He just decides.

Josh Brolin gives Llewelyn Moss grit and intelligence. Moss is no fool—he sets traps, plans escapes, and holds his own. But in this world, smart isn’t always enough. His struggle feels real because he fights not just for the money, but for the belief that maybe, just maybe, he can outplay fate.

Tommy Lee Jones delivers a masterclass in quiet devastation. His Ed Tom Bell isn’t broken—but he’s tired. He’s watching a world fall into chaos, and all he can do is narrate its descent. His voice opens and closes the film like scripture, and his final lines leave you wondering if there ever was an order to the world at all.

No Country for Old Men is often described as a neo-Western, but it plays more like a philosophical thriller wrapped in a cowboy’s coat. There are no sweeping scores. No epic showdowns. In fact, there’s hardly any music at all—just the wind, footsteps, gunshots, and silence. That silence becomes its own kind of tension.

The cinematography, led by Roger Deakins, captures the vast emptiness of the American Southwest. There’s nowhere to hide. Every frame feels sunburned and fatal. You don’t just watch the violence—you feel it coming long before it arrives.And when it does, it’s fast. Brutal. Unsentimental.

At its core, No Country for Old Men is about control—and the illusion of it. Every major character believes they’re playing the game right. Moss believes he can outrun danger. Chigurh believes he’s the instrument of fate. Sheriff Bell believes he can make sense of it all.

But the film offers no comfort. There are no lessons. No redemption arcs. People die off-screen. The hero doesn’t get a final confrontation. The villain walks away into the distance, injured but alive.

This isn’t lazy storytelling. It’s deliberate. The Coens are challenging you to confront the randomness of real evil—the kind that doesn’t monologue or make mistakes. Just like life, justice doesn’t arrive when or how you want it to.

No Country for Old Men swept the 2008 Academy Awards, winning Best Picture, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor (Bardem), and Best Adapted Screenplay. But its impact stretches beyond trophies.

It influenced a new wave of subdued, cerebral thrillers. It reminded Hollywood that silence can be scarier than music. That evil doesn’t need explanation to be terrifying. And that sometimes, the story doesn’t end with a bang—but with a man describing a dream and waking up, alone.

No Country for Old Men remains one of the most gripping, thought-provoking, and disturbing films of the 21st century. It doesn’t hand you meaning—it makes you dig for it. And what you find isn’t always comforting.Because in the end, some countries—some times—simply aren’t made for old men. Or good ones.

-1751442617-q80.webp)